WHERE DO WE START?

‧₊˚❀༉‧₊˚.‧₊˚❀༉‧₊˚.‧₊˚❀༉‧₊˚.‧₊˚❀༉‧₊˚.‧₊˚❀༉‧₊˚.‧₊˚❀༉‧₊˚.‧₊˚❀༉‧₊˚.‧₊˚❀༉‧₊˚.‧₊˚❀༉‧₊˚.‧₊˚❀༉‧₊˚.

Black hair has a meaningful and complex history. From its vibrant cultural roots in Africa to its strength against discrimination in the United States, there is no doubt that it is a symbol of survival, resistance, and celebration. Read on to learn about how it became such an important socio-cultural symbol in the Black community.

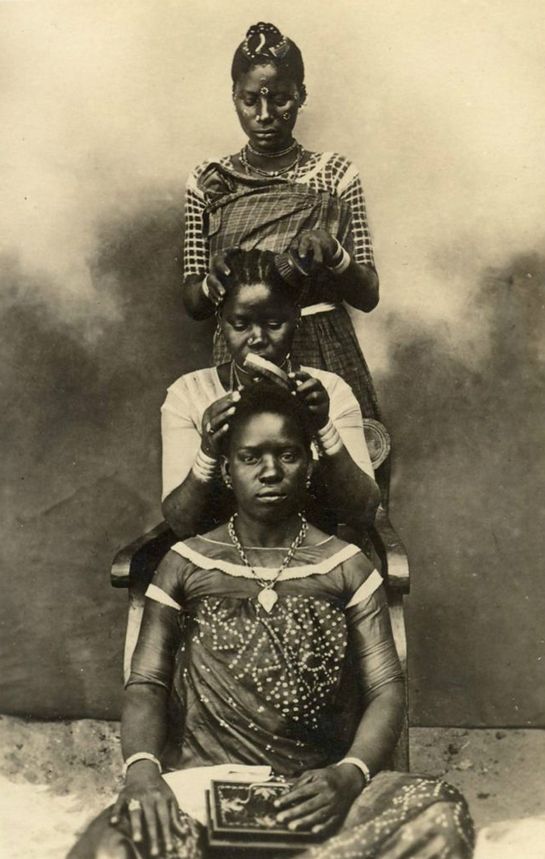

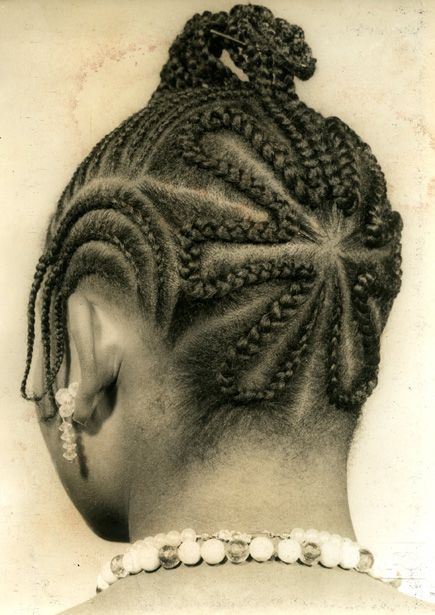

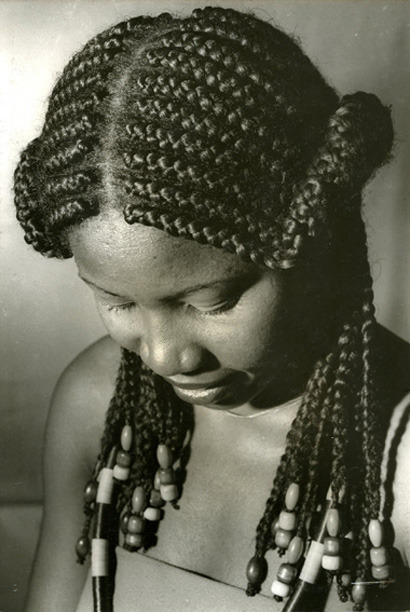

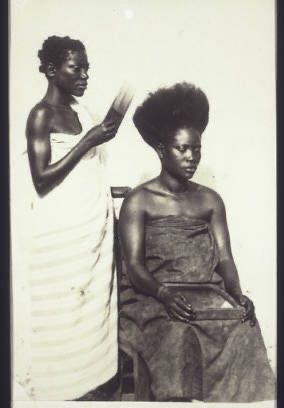

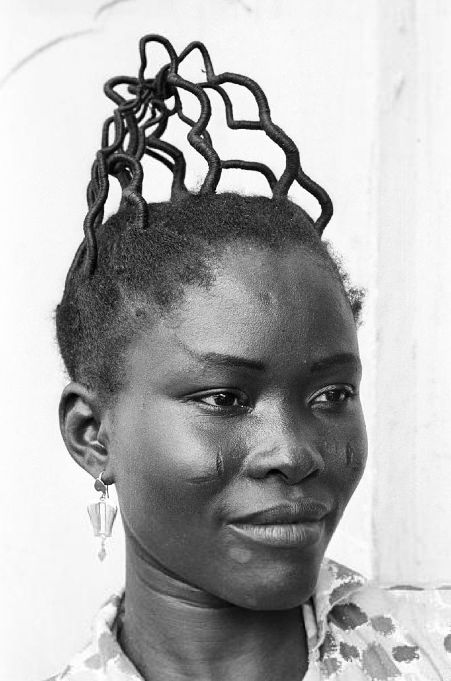

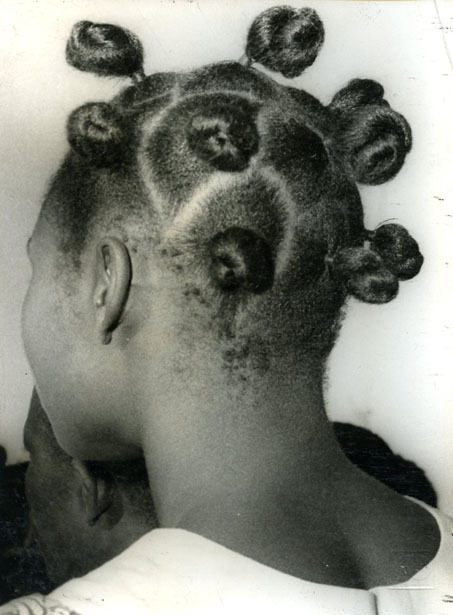

African Beginnings

In many African societies, hair was a sacred cultural and spiritual symbol. Braids and other intricate hairstyles were often worn to signify marital status, age, religion, wealth, and rank in society. In some cultures, a person’s surname could be ascertained simply by the hairstyle they had. Even things used to adorn the hair of African people, like beaded braids and special headdresses were part of the unique essence of Black hair. These adornments were typically reserved for royalty or those of higher rank within the society. Seeing as the head is the highest part of the body, many cultures believed hair connected them with the divine (gods and spirits). Intricate braided styles could take hours, even days, thus, hair styling was a social ritual many families and friends bonded through. This rite of passage still exists today, as many Black people relate to the laughter and stories that are shared when getting their hair done.

Arrival in the United States

Given the transatlantic slave trade, the creation of chattel slavery given the was the turning point for the perception of Black hair, and is what gives the topic its difficult complexity. One of the first things slave traders did to their new cargo was shave their heads. Interpretations include that this was done for sanitary reasons, as hair could become a hassle to take care of when transporting enslaved people. However, the effect of this was far more impactful and insidious. Shaving the heads of the African people they attempted to take away centuries of culture that had existed before their arrival. Enslaved people became anonymous chattel, not differentiated by their unique hairstyles. This is particularly dehumanizing because it was clearly intended to strip away the African people's connection to their culture through their hair. When their hair grew back, they no longer had access to the same herbal treatments, oils, and combs from their homeland. Nevertheless, they got creative, using bacon grease, butter, and kerosene as conditioners, cornmeal and dry shampoo, and sheep fleece carding tools as combs.

Gived the lack of agency or free time they had to take care of their bodies, enslaved women began to cover their hair with rags. Not only were their bodies treated as objects and exploited for pleasure by their enslavers, but even their hair suffered from the grip of white supremacy. In this era, braiding no longer took place in the form of intricate designs, because they didn’t have the proper tools, and lacked the time needed. However, enslaved people used the simple braids to hide rice or seeds in their hair before a long journey. Additionally, as the idea of race continued to gain its complexity, that contributed to the perceptions of Black hair at this time. The term “good hair” made its way into the lexicon, referring to hair that is wavy or straight in texture, and therefore considered beautiful. In the 1900s, more cultural messages began to idealize the version of Black hair that would provide black women with the most upward mobility and economic opportunities. Such cultural messages emphasized the idea of “good hair”, which politicized hair even more. Madam CJ Walker was a key figure in the rise in prominence of hair relaxer, a chemical process that permanently straightens curly hair. Because she was a black woman herself, her product sanctioned the act of straightening. With this introduction of chemical straightening, Madam CJ Walker introduced a way for African-American women to escape the subordination that wearing their natural hair unfortunately brought. However, at what cost?

Modern Day

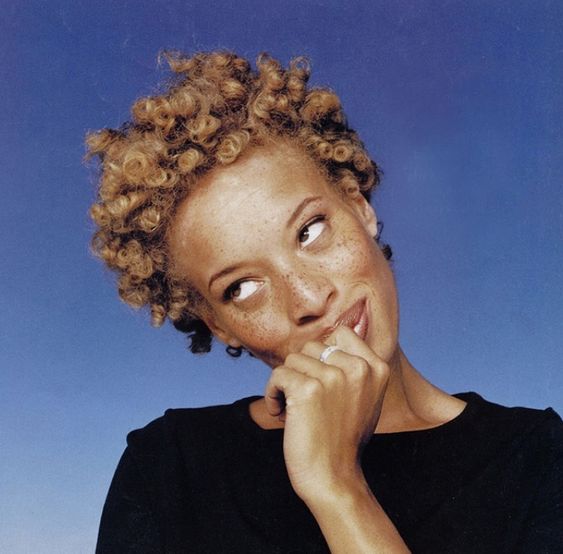

Society’s perceptions of Black hair influence how Black people are treated today. For example, the mentality of “good hair” and “bad hair” has been passed down for generations. The Perception Institute’s 2016 “Good Hair” Study suggests that a majority of people, regardless of race and gender, hold some bias towards Black women based on their hair. Additionally, in 2020, Duke University found that Black women with natural hairstyles were perceived as less professional, less competent, and were less likely to be recommended for job interviews than candidates with straight hair, who were viewed as more polished, refined and respectable. The idea of “good hair” being more beautiful than more curly textures is perpetuated by cultural messages that idealize this version of hair and offer treatments and products to achieve it. Also, product placement in stores is one example of how hair standards are normalized within a larger culture of beauty Many stores put smooth hair products in the “beauty” section, while curly hair products are in the “ethic” section. Subliminally, this sends the message that natural hair is inferior, less desirable, and less beautiful.

“Don’t remove the kinks from your hair! Remove them from your brain!”

- Marcus Garvey

The 2000s brought the 2nd wave of the natural hair movement, spurred by films and the increasing prominence of social media. Youtube channels and natural hair blogs empower Black women to wear their natural hair. They allow them to discuss hair-care journeys, share hair tutorials, and connect with other women who are experts at caring for natural hair, and those who are just starting out. Black hair does not all look the same. There are various textures, curl patterns, lengths, colors, and porosities. There is no one way to treat it, all of that is up to the individual. All Black hair is beautiful.